Gary Winogrand (1928-1984) is an iconic street photographer, so prolific he has been called “the first digital photographer” but in truth he wasn’t a fan of being instant.

In fact, many fans think he would have absolutely hated Instagram and everything it stood for, but perhaps they’re not looking at the whole picture (sorry).

Winogrand was famed for his shots of Manhattan in the 60s, had a unique approach to processing his images which simply wouldn’t work now: He didn’t look at them for a year or longer. When he died in 1984 he had the better part of 500,000 images in his collection he’d never even seen. Why? Because he had established a workflow designed to remove his own personal emotion, and so pick better images.

Sometimes photographers mistake [their] emotion for what makes a great street photograph.

Gary Winogrand

His theory was that, if he didn’t look at the photographs for a while, he would be less influenced by his own feelings on the day they were shot. If he’d been in a good mood, he might think the picture better than it was. With time to forget what was going on, approaching the contact sheet cold, he’d make better choices. He has explained as much to his students, including O.C. Garza, who describes more of his experiences here.

Why Winogrand wasn’t ‘instant’

It definitely wouldn’t work for everyone, but the process of removing your own emotion and excitement from the photography you share has clear editorial benefits. Winogrand shot a lot of photographs – over 1 million during his lifetime according to Michael David Murphy, or about 76 stills a day while he was shooting.

Those numbers are pretty big even by modern standards when showing and sharing is free. When you’re shooting film, developing with chemicals, and printing on paper some kind of editorial control is the only way to prevent bankruptcy.

Since photographers are, for the most part, their own editors – at least in the first instance – separating personal feelings from the moment of capture and the image is tricky. Time is a great solution (at least if your memory is anything like mine).

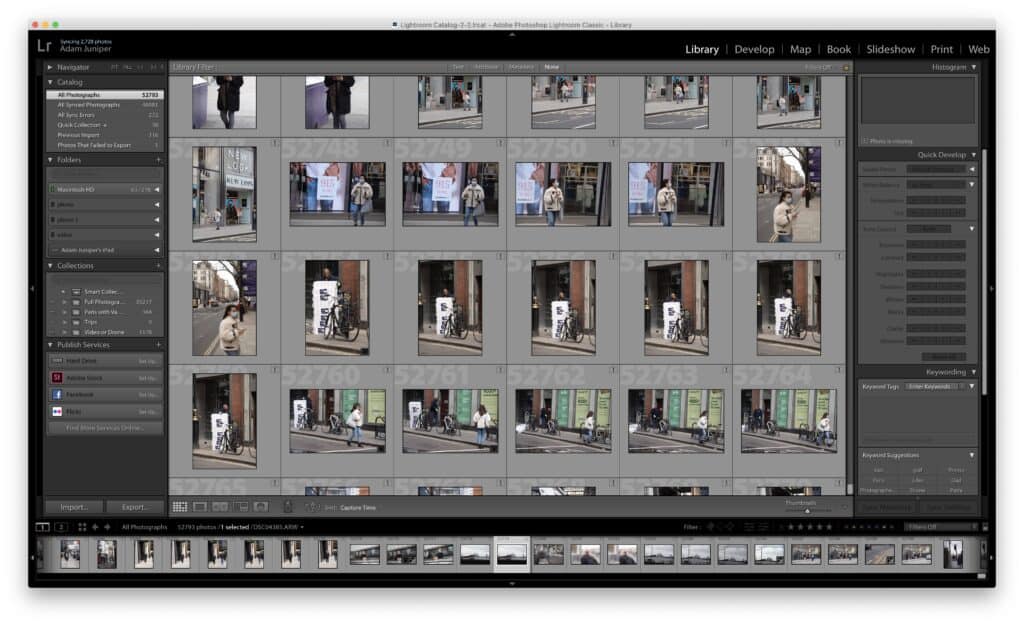

If your work isn’t time-critical – and street photography for art or for a hobby is a great example – then it’s easy to take advantage of the same principle. Shove your day’s photos into Lightroom and forget about them for a bit.

Why the world is instant

Not an especially difficult one this; digital tech has eliminated the main mechanism by which Winogrand was able to put his captures on pause – undeveloped film. Once you’d shot off images it’s hard not to view them instantly, and most cameras are now connected to the point of instant sharing (in fact most cameras are phones).

That means it takes a degree of self-restraint not to immediately look at your pictures and share them. It’s also, arguably, good practice to do so – at the very least to add captions/metadata so you know what you shot. Writing on the side of film canisters with a permanent marker was never that easy or successful an approach. Some things are better.

But you can still leave the images on a hard drive or storage location indefinitely before coming back to process them, and that might be the time for a more honest appraisal.

Instagram actually does learn from Winogrand

At first, the idea of Instagram would seem to the anthesis of Winogrand’s one-year-wait but, in a way, Instagram has evolved a similar approach: Stories v Feed.

At first, the platform was a free-for-all; it was very much down to the user whether they used their feed to tell a living story or to simply post their finest work. Was it a portfolio or purely visual social media? Your account was whatever you wanted.

As the platform developed, the addition of the Stories feature essentially took that choice away – your living social content should go in your Stories and – logically if not explicitly – the Feed is now reserved for the better quality shots.

By subtly declaring that your Feed is for posts you’ve put some time and thought into, Instragram has effectively encouraged you to take your time over your posts, and to self-edit. It doesn’t have to be a year, but there’s no reason not to learn this from Winogrand.

Winogrand ain’t woke

Because Winogrand had a novel and successful approach to editing, doesn’t mean you need to copy everything from him.

To be clear, there is no specific accusation here, but it has to be said that Winogrand’s oft-seen ‘surprise’ approach might have more detractors now than it did at the time. His contemporary, Diane Arbus, would spend time acquainting herself with her subjects, while Winogrand is known for his ‘gotcha’ surprise style.

Of course, it’s perfectly possible to argue that Winogrand’s style is the epitome of street photography. That it is street photography. But times are changing. It is definitely not the only approach, and in some cases, it can pose a risk to your career – street photographer Tatsuo Suzuki was, apparently, dropped as an ambassador for Fujifilm for having a too “in your face” style.

Further Reading (external links)

- 10 Iconic Images by Gary Winogrand – some examples of his work on pbs.com (sadly I don’t have the rights).

- My Street Photography Workshop with Gary Winogrand Mason Resnick, a photographer, describes going on a workshop with Winogrand in 1976 for Black & White World.